Archaeology and history is not always a black and white matter. If archaeologists unearth a 2,000 year old artifact, should it belong to the land it came from, the people who find it, or the museum that preserves it? This question is the core of the debate of repatriation in archaeology.

What is Repatriation?

Repatriation: the act of returning cultural artifacts, human remains, or sacred objects to their place or community of origin.

It may sound simple, but in reality, repatriation is far more complex. Many objects displayed in modern museums did not arrive through peaceful means. During periods of colonial expansion, war, and political unrest, artifacts were often taken through looting, coercion, or exploitative excavations. Others were removed under legal systems that favored colonial governments while disregarding the voices of Indigenous and local communities. In many cases, this extraction extended beyond objects to include ancestral human remains, taken for scientific study or public display. Over time, these cultural materials entered museum collections through donation, purchase, or institutional transfer.

Since the late twentieth century, countries and institutions have begun taking steps to legally enforce the return of unlawfully acquired cultural materials. In the United States, repatriation is guided in part by the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), passed in 1990. This law requires federally funded institutions to identify and return human remains and certain cultural items to affiliated Native tribes. Internationally, agreements such as the UNESCO 1970 Convention seek to prevent the illicit trade of cultural property and encourage the return of stolen artifacts, though enforcement and compliance varies.

Repatriation is rarely a simple transfer of objects. It often involves extensive negotiation, documentation, and collaboration between museums and descendant communities. These processes raise broader and more difficult questions: Who has the right to tell history? Who decides how cultural objects are cared for, interpreted, or displayed? And what does justice look like when the past cannot be undone?

Arguments for Repatriation

- Repatriation is a necessary step toward historical justice, as many artifacts were removed through violence, coercion, or unequal power structures and were never willingly given. One well-known example is the Benin Bronzes, which are thousands of bronze plaques and sculptures violently looted by British forces during the 1897 raid of Benin City and later dispersed across European and American museums. For descendants of the Edo people, these objects are not simply works of art, but historical records that preserve their lineage, political authority, and cultural practices cruelly disrupted by colonial invasion.

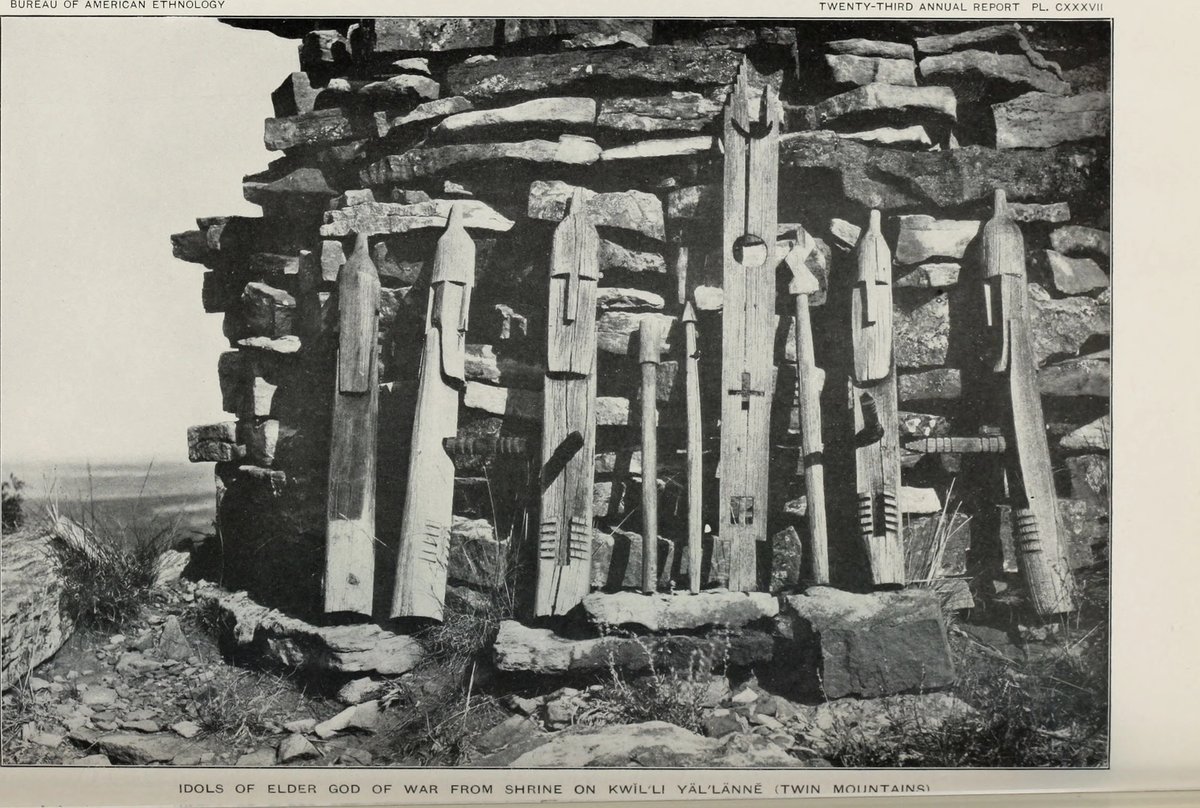

Collection of Benin Bronzes at the British Museum. Image Source. - Many cultural objects are not merely historical or artistic, but hold deep religious, ceremonial, or ancestral significance that requires cultural context to be properly respected. Funerary items or sacred ceremonial objects belonging to Native American tribes, for example, have often been stored or displayed in museums without regard for their spiritual meaning. Repatriation allows communities to care for these objects according to their traditions. This can be seen in the return of the Zuni War Gods (Ahayu:da). The Zuni Pueblo traditionally carved two war god figures and placed them on sacred mountains, where they were meant to weather naturally as spiritual protectors. When these figures were removed and stored in museums, their intended purpose was violated. Their repatriation restored both spiritual practice and cultural autonomy.

A Zuni War God shrine. Image source. - Refusing to repatriate artifacts can reinforce modern forms of colonialism and perpetuate disrespect toward descendant communities. This is especially evident in cases involving human remains, where repatriation is essential to restoring dignity and humanity. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Māori tattooed heads (mokomokai) were taken through looting or coercion and sold to European collectors who treated them as scientific curiosities rather than as ancestors. Their display in museums stripped them of identity and humanity, while repatriation has allowed Māori communities to properly mourn and honor their dead.

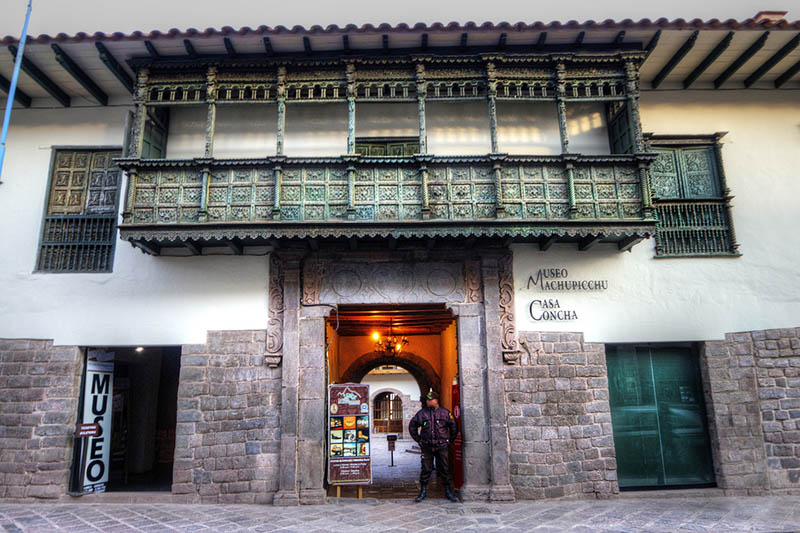

General Horatio Gordon Robley, a British army officer, and his mokomokai collection. Image Source. - Repatriation also does not require the loss of historical knowledge. Communities can, and often do, collaborate with museums and governments to ensure continued research and public education. A prominent example is Yale University’s return of thousands of artifacts excavated from Machu Picchu by Hiram Bingham in the early twentieth century. Following repatriation, Yale and Peru established joint research agreements, and a museum and research center was built in Cusco to study and display the artifacts. In this case, repatriation expanded access to knowledge rather than limiting it.

Museo Machu Picchu, Casa Concha, where the artifacts returned by Yale are currently located. Image Source. - Finally, repatriation allows communities to reclaim control over their own histories and reintegrate cultural objects into living traditions. In Scandinavia, Sámi shamanic drums were confiscated by Christian authorities and confined to museum collections. After their return, these drums became central to cultural revitalization efforts, used in ceremonies, education, and the teaching of Sámi cosmology. Rather than remaining static artifacts behind glass, they once again became meaningful parts of everyday cultural life.

Sámi shaman drum returned by the Danish authorities to the Karasjok Museum. Image Source.

Arguments Against Repatriation

- Keeping artifacts in global museums also increases public accessibility and reinforces museums as institutions for cross-cultural education. Museums like the British Museum house artifacts from Egypt, Greece, Assyria, China, and the Americas in a single location, allowing visitors to encounter diverse cultures side by side. This concentration of material culture enables comparative learning and encourages a broader understanding of global history that may be less feasible if artifacts are dispersed across many countries or institutions.

Egypt collection at the British Museum. Image Source. - Another argument against repatriation is that removing artifacts from major museums may place them in facilities with fewer resources for long-term preservation. Large, well-funded institutions often have advanced conservation technology, specialized staff, and robust security systems that smaller or under-resourced institutions may lack. The Rosetta Stone, a 2,200-year-old granite slab inscribed with Egyptian hieroglyphs, Demotic script, and Ancient Greek, is currently housed in the British Museum despite originating in Egypt. There, it is kept in a climate-controlled case, protected from direct handling, regularly monitored by conservation specialists, and secured against theft or damage. Supporters of retention argue that such conditions maximize the artifact’s physical longevity.

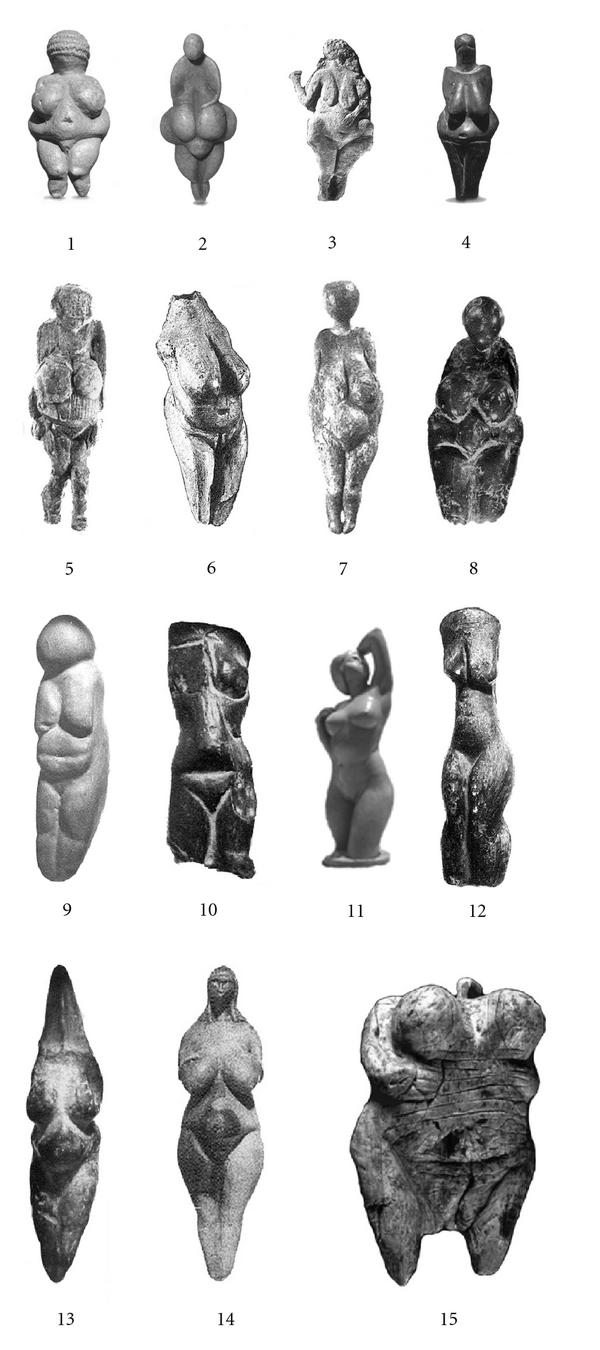

The Rosetta Stone at the British Museum in London. Image Source. - Another common argument is that some artifacts constitute shared human heritage rather than the property of a single modern nation or group. Certain objects predate contemporary borders and cultures, complicating claims of exclusive ownership. For example, Venus figurines from the Upper Paleolithic period (approximately 40,000–10,000 BCE) have been found across Eurasia. These small female statuettes are often interpreted as expressions of early human ideas about fertility, motherhood, or spirituality. Because they do not belong to a single identifiable civilization, they are studied internationally as evidence of early human behavior rather than as cultural property tied to one modern society.

Venus figurines discovered across Eurasia. Image Source. - Opponents of repatriation also argue that dividing artifacts among different communities or restricting access may limit academic research and slow scholarly progress. Some culturally sensitive objects are accessible only to specific community members, which can significantly limit outside study. Katsina (kachina) artifacts from the Hopi Tribe in Arizona, for instance, hold deep religious significance, and access to them is often restricted to tribal members. While these limitations are culturally appropriate, critics argue that they reduce opportunities for broader academic analysis and cross-disciplinary research.

Hopi Katsina figures. Image Source. - Finally, determining rightful ownership can be legally and historically ambiguous due to shifting borders, colonial governance, and competing narratives. The Parthenon/Elgin Marbles exemplify this complexity. Sculpted for the Parthenon in ancient Athens, portions of the sculptures are housed both in the Acropolis Museum and the British Museum. Britain maintains that the marbles were legally acquired under an Ottoman-era decree, while Greece argues that true consent was never granted and that the sculptures are integral to Greek cultural identity. This unresolved dispute highlights the difficulty of establishing clear ownership when historical authority and modern national identity do not align.

The Parthenon/Elgin Marbles at the British Museum. Image Source.

Together, these arguments show that repatriation is not a clear-cut matter of right or wrong, but a debate shaped by access, preservation, and differing interpretations of cultural ownership. Because every artifact has its own history and circumstances, there is no universal solution. How do you think cultural materials should be preserved and shared? Join the conversation in the comments below!

Works Cited:

- “Albion College Returns Sacred Zuni Artifact to Its Home.” Albion College, 2023, www.albion.edu/news-article/home-at-last-sacred-zuni-artifact-returns-to-where-it-belongs/.

- Cascone, Sarah. “MFA Boston Returns Two Benin Bronzes to Nigeria.” Artnet News, 22 Jan. 2025, news.artnet.com/art-world/mfa-boston-benin-bronzes-restitution-2662790.

- “The Elgin Marbles.” EBSCO Research Starters, EBSCO, www.ebsco.com/research-starters/anthropology/elgin-marbles.

- “Kachinas.” Cameron Trading Post, www.camerontradingpost.com/kachinas.html.

- “Peru–Yale University Dispute.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peru%E2%80%93Yale_University_dispute.

- “The Return of a Sámi Drum.” Library of Congress Blogs, Library of Congress, 14 Feb. 2022, blogs.loc.gov/law/2022/02/return-of-a-smi-drum/.

- “Rosetta Stone.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rosetta_Stone.

- “Toi Moko.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toi_moko.

- “Venus Figurines.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Venus_figurine.

- “What’s On at the British Museum 2024–25.” The British Museum, www.britishmuseum.org/blog/whats-british-museum-202425.